As a high school student, I regularly accessorized my outfits with a Jewish star necklace. I could often be found wearing t-shirts with Jewish and Israeli symbols on them, and at one point ironed a decorative Israeli Defense Forces patch onto my backpack. I was proud of my Judaism, and it became increasingly important for me to display it publicly. As with many identity-defining attributes, I wanted my outsides to match my insides. Wearing insignia identifying oneself as Jewish is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that speaks to generational privilege and an ability to claim this identity without fear of retribution, but can also be a source of contention for many. For every impassioned think piece about why we should wear our stars proudly and walk through the world without fear, there’s an equally compelling counterpoint that speaks to legitimate concerns about personal safety that are assuaged by taking this one step to blend in and assimilate.

As Jewish educators in 2021, we are educating learners who are coming of age during a disturbing resurgence in antisemitism and anti-Jewish sentiment. The choices that they make about how to present Jewishly in public are at once deeply personal, while also being a matter of collective concern and communal soul searching. After all, we as educators champion having pride in one’s Jewish identity. It only makes sense that a generation of individuals who are proud, engaged, and confident in using their voices, would be excited to show their inner selves in their external appearances. At the same time, the uptick in antisemitism that has colored the coming-of-age experiences of Generation Z-ers over the last few years has sometimes resulted in adolescents who are more comfortable keeping their Judaism inside.

Rachel is a high school sophomore from Texas. She has been involved in her synagogue, but generally walks through the halls of her public school knowing that she’s one of three Jews in the building. Rachel shared the intentionality behind her decision to wear a particular Jewish symbol. She decided to wear a chai necklace, a symbol of Hebrew letters representing the word meaning “life.” By opting for this symbol instead of the better-known and more easily recognized Star of David, Rachel sought to use her sartorial choices to start conversations. “I got the chai because it’s a way to show my faith to others. People who aren’t curious won’t ask. But because it’s not a Star of David and everyone doesn’t know what it is, if they’re curious enough and they do ask, there’s room for us to have a conversation.”

Zachary is a student at a Jewish day school in Maryland. “After the shooting [at Congregation Tree of Life in Pittsburgh] I started wearing my kippah more in public. I take the metro to school every day, and I wear my kippah. Sometimes I run into other Jewish people, and it’s fun to have a connection. But I understand people who are scared of something happening when you look Jewish in public. For me, I feel like it’s better to show that we’re here, we’re not going anywhere, we’re still Jewish, and we’re going to stay Jewish. There’s not anything anyone’s going to do about it.”

As Jewish educators, we often describe part of our mission as meeting learners where they are. In the case of today’s adolescents, that can mean any number of things, including showing up in person, on Zoom, and on an ever-changing array of social media platforms. Adolescents spend their time in a combination of in-person and virtual spaces, and in each environment there are choices to be made about what it means to present as Jewish. Lia, a high school senior from Ohio, shared that, “I used to include lots of stuff about being Jewish online. I love baking hallah, and I’d put it in my Instagram stories, and I had a TikTok go viral about lighting the Hanukkah candles. But then I started getting hate. I’d post something about Shabbat, and people would tell me to go into the ovens with my hallah. So, I stopped displaying myself as specifically Jewish. Now I’m just someone who bakes bread.”

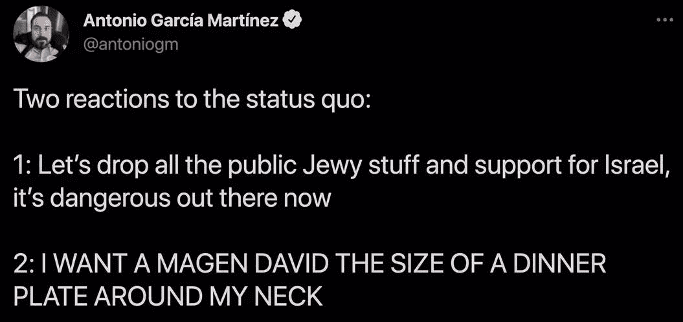

In June of 2021, a meme circulated on social media:

When it comes to presenting Jewishly in public, every choice that each individual makes is deeply personal and legitimate. If someone is frightened for their safety when they claim their Judaism in physical ways, or if they don’t want to be on display as representatives of the Jewish community and opt to fly under the radar, this is not indicative of Jewish shame. Rather than being a commentary on the individual, it’s an indictment of the society that creates the environment in which we feel that being a Jew is something that needs to be somehow private. Likewise, for those who choose to present loudly and proudly, this can be a beautiful thing, particularly when it’s done for the right reasons. To show one’s pride is great—when it’s on your own terms. But for someone’s Judaism to manifest purely as a statement of defiance to detractors is its own potentially fraught reality.

The decisions that adolescents are making about presenting Jewishly in the face of rising antisemitism are informed by instinct, lived experiences, and social norms. Part of the role of the Jewish educator is to be a conduit for this transference of Jewish pride. Our pedagogy can help shape and influence if and how our learners choose to claim their Judaism in public and virtual forums. In our work, we regularly share the beauty, complexity, and meaning-making that Judaism provides. But are we intentionally connecting the lived experiences of Judaism, however they manifest for our learners, with what it means to carry oneself Jewishly in a world where that means being a minority, visibly or otherwise?

“Judaism should be a joyous experience. Antisemitism isn’t, and shouldn’t be, our major raison d’etre when it comes to being Jewish. We take it seriously, of course. But if it becomes what defines our Jewish identity, they win.” Lily, a high school senior, summed up her perspective succinctly. Pride is encouraged and championed, always. But a Judaism based on defiance is neither sustainable nor transferable. If the response to antisemitism is focusing all of our efforts on countering hatred and detractors, learners may find real meaning in their activism and self-advocacy, but they run the very real risk of losing sight of the why behind the what. Any identity that is based on what it runs counter to, rather than the value that it brings lacks sufficient grounding. So when Jewish sartorial choices are made, whether they are for religious observance or cultural adherence, their value to the wearer comes from how they experience embodied Judaism, not in how others react to their choices.

People have lots of guesses about what the hardest and best parts of our jobs as Jewish educators are. Among the elements that others consider to be top contenders for the hardest, there’s recruiting participants from an over-programmed population, dealing with the sometimes conflicting demands of parents and learners, never having enough time, and limited resources. All true. Likewise, some of the top guesses about the best parts are making an impact on young people, constantly learning new things, participating in immersive experiences, and being able to align my passions, values, and profession. Again, all true. But the at-once hardest and best part of this job is being an authentic Jewish personality, a role model, with flaws and questions and ingrained truths, that our learners can relate to, and be challenged by, and learn from.

For those who are coming of age during the resurgence of hate, and those who care about them, allowing for the gray area between the black and white of right and wrong to be a place of meaning-making will be critical. So too will be finding the authentic truths that guide them in their life journeys. As for where that leaves the status quo with regards to antisemitism, the story will continue to unfold.

Samantha Vinokor-Meinrath is the Senior Director of Knowledge, Ideas, and Learning at the Jewish Education Project, and regularly teaches and consults on topics relating to Jewish education, Generation Z, and identity development. Dr. Vinokor-Meinrath’s forthcoming book, #antisemitism: Coming of Age During the Resurgence of Hate, focuses on the impact that antisemitism has had on the Jewish identity of Generation Z-ers.

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.