A Holistic Approach to Cultivating Jewish Spirituality in Jewish Day Schools

Yael Krieger is the Associate Head of School of Oakland Hebrew Day School. Previously, she spent 11 years as Director of Teaching and Learning at the Jewish Community High School of the Bay. She holds an M.S. in Urban Education and is currently a Fellow in the Mandel Educational Leadership Program.

Although I have been a parent at my school for the past five years, in August, I became the Associate Head of School of Oakland Hebrew Day School, a Modern Orthodox, Bridge-K through eighth school in the Bay Area. One of my first responsibilities was planning the teacher in-service week. As I was approaching the transition from a place of observation and learning, I relied heavily on the structure of the previous year, which quickly resulted in my ruminating over the fact that the past year’s schedule had ten minutes of mindfulness beginning each day. I could feel my own insecurities and self-consciousness rising as I asked myself what it would mean as a leader to ask my teachers to engage in a practice with which I personally didn’t feel comfortable. Following the passion and faith of the Head of School, I kept it in the schedule, and she led the ten-minute sessions. I was pleasantly surprised to find that despite being in a room of people I didn’t really know, I was able to engage and feel grounded in the practice.

While I took on this new role anticipating a steep learning curve, my most profound and unexpected growth has been around understanding the value of and embracing a holistic and communal approach to Jewish spiritual education. OHDS begins from the assumption that cultivating spirituality in our students is one of our highest responsibilities as a Jewish day school, and that a strong spiritual core is crucial to their Jewish and social-emotional wellbeing. Our experience has taught us that effective and meaningful spiritual education has to be grounded in 1) the instilling of practices rather than content, 2) attention to the ethos and school ecosystem as a whole, and 3) partnership and collaboration with families.

Two years ago, the school developed eight guiding principles that contribute to fulfilling our vision of “Thriving Students. Thriving School.” These principles—sensitivity to holiness, inner calm, joyful inquiry, connective relationships, aware and active bodies, creativity, care for the wider world, and confident academic readiness—guide us in all of our decision-making processes and serve as our compass of “What Matters Most.” It is telling that the word “spirituality” does not appear, as the principles reflect core elements and practices necessary for developing spirituality in our students—they speak to how we understand the means of cultivating spirituality.

One of the categories from which our middle school students choose Jewish Studies classes is called “Spirituality and Community.” This year, one class explored the issue of tokheha, rebuke. The course description for this class was as follows:

Though it’s often an uncomfortable thing to do, it’s an important mitzvah to resolve our interpersonal conflicts by speaking openly and directly with each other. How can we do this in a way that honors each person’s dignity and supports connection and peace? How can we turn our conflicts with others into opportunities for building up our relationship with them? In addition to studying foundational texts of our tradition, we will also workshop, role play, and practice the art of giving and receiving tochacha (rebuke).

Both the category and the course description reflect the importance of practice within the context of community as a foundation of spiritual education. For students, teachers, and families to feel comfortable embracing the practices, the language, and the intention of spiritual education, this is made explicit. The language we use serves as a tool for normalizing the work and making it feel more accessible. In fact, one of the categories on the report cards of our oldest students assesses the level of independence with which they “reflect on issues of spirituality in writing and class discussions.”

While the language in our report card and our Jewish studies courses reflect topic-specific areas where spirituality education happens intentionally, spiritual practices cannot be effectively embraced by students if only isolated to specific classes or single teachers. We find that its reinforcement from multiple directions is what creates the fertile ground needed for cultivating spirituality with students, teachers, and families. This past summer our entire faculty read The Awakened Brain, which very compellingly describes the brain’s ability for learning how to think spiritually. The book describes how the language we use, the way we speak to each other, and the questions we ask each other are all tools that help enhance our ability to engage in the world spiritually. As discussions around the idea of spirituality became more akin to something like “how do we develop a growth mindset,” we began to see how simply, the language we use when speaking about, or with, students is itself important to the process of teaching spirituality.

As part of our middle school advisory program, our students engage in a bi-weekly havurah called Lev Hashavua. Lev Hashavua is a practice of learning and sharing developed by Lifnai v’Lifnim, which grew out of the collaborative work of educators and psychological practitioners engaged in Hasidic education. In Lev Hashavua, the students sit in a circle, learn together, and engage in authentic conversations where they can be present and speak openly to each other. In each session, one student shares about themselves, and the other students practice the art of reflective listening. The goal is to create genuine connections and build a shared language.

Since we believe that the success of our spiritual education also relies on our teachers’ ability to hold a deep belief in the capacity of our students to develop as spiritual beings, Lev Hashavua is also held twice a month for a group of twelve teachers. The more our teachers can experience space and holiness in their own work, the more this spiritual language can filter down to the students both directly and indirectly.

We sometimes encounter reluctance, resistance, or cynicism about Lev Hashavua, with some students jokingly referring to it as group therapy and others simply disliking the work in spiritual practice, but our consistency and commitment with which we pursue it have opened the door to some special moments. Recently, Purim celebrations interfered with our regularly scheduled middle school Lev Hashavua session. The teacher who typically leads these sessions happened to wander into the library and find an 8th grader there who asked him, “Are we doing Lev Hashavua today?” Wary of the question being less than innocent, the teacher tentatively responded, “I’m afraid not. Why do you ask?” The student’s response, “‘cause I really need it,” led the teacher to invite real and honest sharing from this student, and the two of them engaged in the practice of spiritual sharing and connection.

Tefillah also holds rich potential for spiritual cultivation, a potential which is often unfulfilled, but the regularity of the practice (which sometimes dulls the spiritual impact) helps students build resilience, commitment to practice, and the possibility for those meaningful spiritual moments. Our Middle School boys are required to wrap tefillin every day. This practice may not feel spiritually important or meaningful on a daily basis, and we openly discuss this with students, but the muscle memory and the fluency of practice create the framework for those moments in which they are ready for it to be a spiritual experience.

Once spirituality education is more firmly established as being about regular practices rather than transitory experiences or content learning, it becomes easier to couch spirituality into the domain of communal responsibility. Once a week we offer our middle schoolers tefillah electives which include more overtly “spiritual” options like mindfulness and meditation. The most desired option, however, is the tefillah leadership one, where the older students get to spend their tefillah being mentors in younger grades. Here they can fully embrace their own capacity to feel purpose beyond themselves, enhancing their ability to understand that helping to facilitate a spiritual experience for others is itself a meaningful spiritual practice.

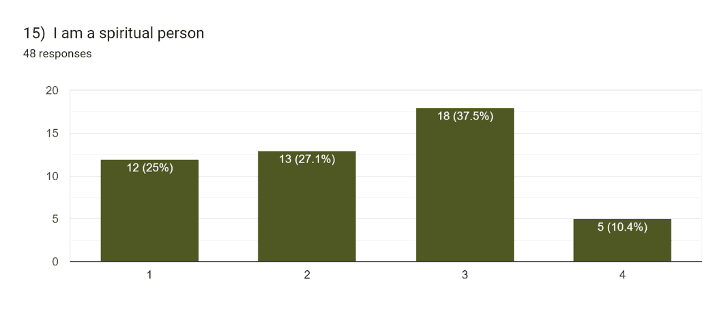

Spiritual development—whether in kids or adults—can be hard work. We are never surprised when we hear pushback from students or sense their reluctance or discomfort in the practices. In a school setting, it requires faith and belief that the children are both able to do the work, that it is ultimately worthwhile, and that it’s okay for students to not feel excited about the work all the time. We recently conducted a survey of our 4th – 8th graders focusing on the student’s social-emotional experience. Students rated statements from 1-4 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). One of the statements they were given was, “I am a spiritual person.” That nearly half of ten-fourteen year-olds answered in the affirmative, speaks volumes to the seeds we are planting.

The day after the survey was administered, a 4th grader in a “rose-thorn-bud” go around during class said, “I want to become a more spiritual person.” Simply asking the students whether they saw themselves as a spiritual person had unlocked something, it had planted the possibility that she could be a spiritual person.

Engaging in this work as a school administrator has had an impact on my parenting. I’ve found myself taking home some of the language and becoming more comfortable in talking about spirituality with my own children. This year we launched our first parent Lev Hashavua learning night to give them a taste of what we do. The goal wasn’t to tell the parents about the practices we were doing with the students but to bring parents into the circle of cultivating a spiritual core with their children, and we are exploring ways of bringing parents more fully into a partnership around this.

We do not see spiritual education as optional; it is core to our educational vision. Our commitment to making meaningful change in the spiritual education of our students has driven us to find increasing ways to include it as part of the rhythm of the school, whether it is in a Jewish studies class or a disciplinary conversation. Students encounter the messages of spiritual education reinforced by the many adults in their lives, both in what those adults say and how they model it in their own practices and interactions. Protecting and prioritizing the components that allow for spiritual engagement provides the fertile soil for cultivating innate sacred qualities. Finally, we understand that spirituality is not itself an end goal, but a disposition towards holiness, inner calm, awareness, joy, curiosity, connection, care, and learning.

Yael Krieger is the Associate Head of School of Oakland Hebrew Day School. Previously, she spent 11 years as Director of Teaching and Learning at the Jewish Community High School of the Bay. She holds an M.S. in Urban Education and is currently a Fellow in the Mandel Educational Leadership Program.

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.

Kol HaKavod, Yael, for prioritizing the cultivation of spirituality in our youth and educators. This approach is needed now more than ever. And Mazal Tov on your new position! OHDS is blessed to have you.