M. Evan Wolkenstein is Director of Experiential Education and teaches Tanakh at the Jewish Community High School of the Bay. His teaching is brimming with creativity as he seeks to engage his students deeply in the text and help them find authentic, personal connections with Torah. Most of his work is student-centered and challenges students to explore and generate interpretations of the text. In this contribution, he shares with us one of the multiple projects his students work on in the course of the year.

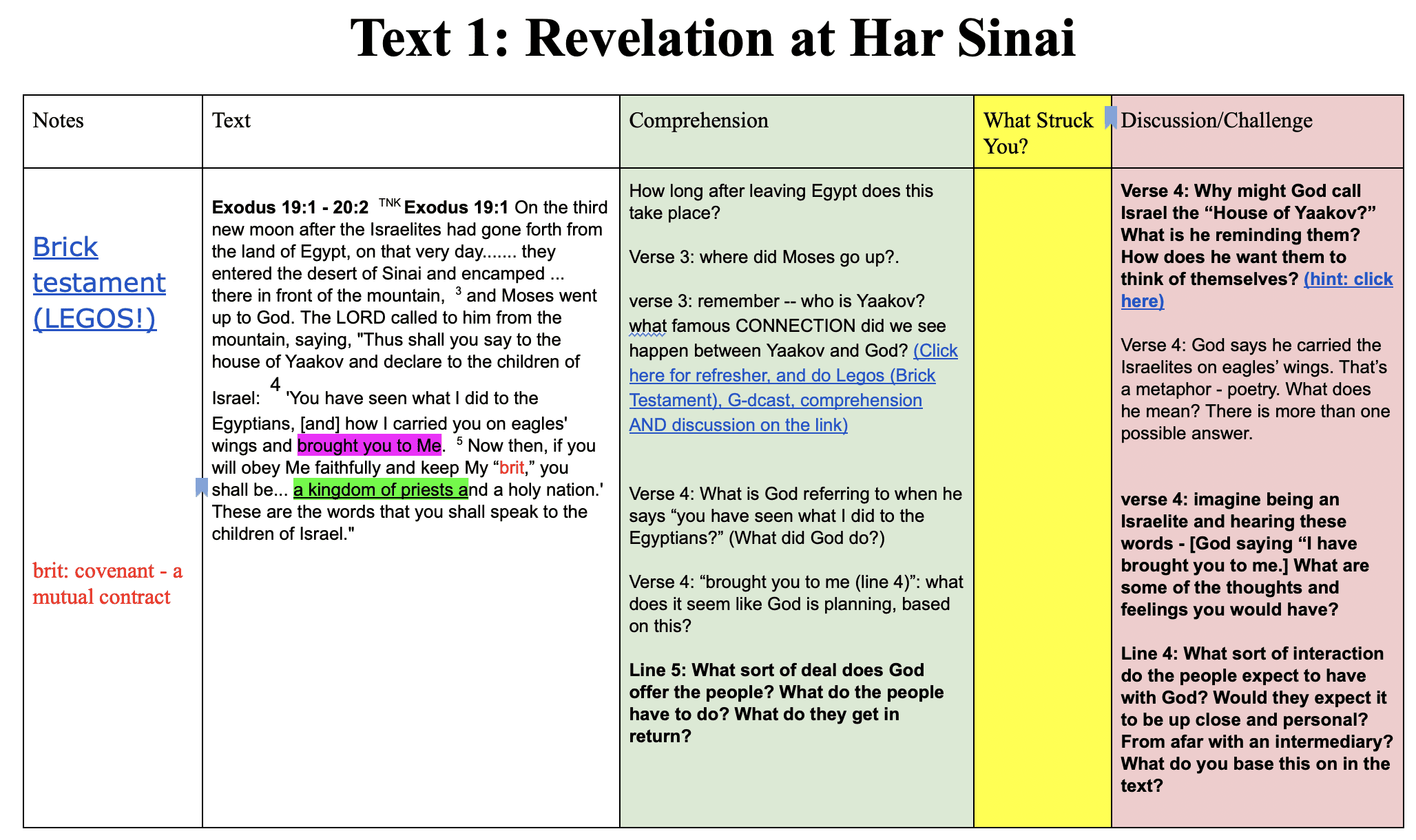

The project is an exploration of the preparations for receiving the Torah at Mount Sinai, Exodus 19. Students engage in a number of different activities as part of their learning. These include studying the text, pursuing thematic approaches to understanding the relevance of the text, journaling, examining visual metaphors, generating ideas through dialog, and artistic expression. Built into the process is a significant amount of student choice, an expectation that students will try different things and refine their ideas over a number of iterations, and reflection.

The project is organized and presented to the students using an interactive Google slide deck. We encourage you to open it, click through it, and play with it to get a sense of what it includes, how it works, and how it helps students navigate through different stages of their project and remain organized through what could and should be a complex and messy project. Jewish Educational Leadership is delighted to share a conversation we had with Evan about this.

Jewish Educational Leadership: Could you give a brief description of what this project is. Just for somebody who’s completely uninitiated, who hasn’t seen it?

M. Evan Wolkenstein: This project is an interdisciplinary exploration of a Torah text, namely the revelation at Sinai. By interdisciplinary I mean that it combines skills needed for close text analysis, along with creative midrash, along with interviewing skills and also applying an art lens, like a contemporary or abstract art lens. All those things go together in this multi-stage project.

Why did you decide to do it that way? What are you trying to accomplish with that?

Great question. For a long time, I had a sense of what was possible to do with learning—how it could generate depth of meaning and how exciting it could be. I kept finding that doing close text reading by itself or just doing an art component was not turning out the rich exploration that I knew was possible. The text study alone felt flat, one-dimensional, and the art lens alone was lacking the deep roots in the text, unmoored and straying into an “anything goes” arts approach. I think that there is a place for that, but that wasn’t my goal. So I began to think that if I could combine them in a way that wouldn’t be confusing for students then it would become greater than the sum of its parts. Once I decided that, I needed an organizing tool, a wayfinding tool for students to work either at their own pace if they were ready for that or in a more guided way if they needed more structure and support.

So is this an in-class assignment or an out-of-class assignment?

Some of it is for sure at home. The interviews, notably, are with somebody who’s a generation or two generations older than them. The interviews are important because the theme of the text as we’re exploring it has to do with relationships, and the challenges of new relationships. And while the students have plenty to say about new relationships and the challenges, my thought was that older generations might have a different perspective that they could bring to bear on the text. So some of it does need to be at home.

That being said, I’ve been moving into a mode of less homework in general. In fact, when possible, no homework at all—trying to do much in class, even if that means changing my expectations of what is possible. So most of it is in class, except for the parts that can’t be. For example, the first chunk of every class might be journaling, sketching, or getting practice in one of the elements that they need to do for the project. If they’re going to be designing that day, the beginning of the class might be a kind of guided exploration.

I’m curious what changes you make, if any, to the physical classroom space in order to facilitate the types of interactions that you’re looking for.

Sure, it’s less to do with what changes I make to the classroom and more to do with what other spaces in the school we explore. At Jewish Community High School of the Bay, we have something called Ever Lab, which is a kind of design lab with easily movable furniture and cushions and things, we have nooks around the second floor of the building where students can cluster, so what we’ll often do is that we’ll do an orientation at the beginning, maybe some journaling, and then a little reflecting. Afterward, I’ll send students off to one of those places, either depending on how far they’ve gone and if they need to work independently or they want more support, they might report to a certain place. If they need to do some pair-share, they might use one of the nooks… so it’s less about changing the classroom which we leave in our format, the circle, and it’s more to do with how we think of the entire floor or even the entire school as the classroom.

Aside from designing this project, what are you doing while the students are doing all this other stuff.

I’m in a help desk mode, walking around and helping with students who are stuck. If students are in dialogue—I’m sitting close to them, but not so close so as to interfere with their conversation, to reinforce the idea that they should be reflectively listening to each other. They see me there, they see me with ClassDojo on my phone, they know that I’m giving them a star on their profile if they’re reflectively listening. I’m providing students who need some art supplies with more art supplies or answering questions; I’m really floating around and just kind of checking in with groups of students to see what they need.

One of the things we noticed is that you provide lots of options for students to “read” the texts, including things like the Brick Testament, Hebrew texts with and without translations, etc. What inspired that? How does that impact the students and their learning? For those who are using one of the alternatives, do you or do they feel like their learning is being watered down because they’re not just working with standard texts?

First of all, I’ve made a pedagogical choice to use an abridged text. I know that is not everybody’s chosen approach and will certainly be legitimately criticized, but I do it to make sure that I can get through the narrative I want to explore in the amount of time that students have the attention span for to have an enriching experience. I’m basically curating the text in a way that allows for lots of possible interpretations. The decision to clip certain elements of the text does close the door on some of the tangents, but that makes sure that we don’t get lost in the weeds. Even though you could say that stumbling over the words can be very productive, I try to remove impediments because there’s enough challenge as it is. So, I’ll hyperlink to images to help the students understand the concepts that are difficult or include a link to the Brick Testament because I found that some students, especially newcomers to Torah learning, have trouble. But again, I’m choosing to have the challenges be in the content and meaning rather than in the decoding.

I link to videos or outside resources that are thematically interesting; I might use Padlet or Wakelet or Symbaloo to aggregate resources. For example, for the Mount Sinai text, there might be five videos of things being plugged into too much voltage, or things melting down because so much sunlight is being focused on it, or movies that represent the concept of too much power for something to handle. I chose these because one of the themes that the students might choose is that the Sinai experience represents the dangers of too much intimacy or too much connection too fast, which can create a meltdown or a collapsing of boundaries. So, they view videos that might enlighten them on what that might look like. The texts are linked to some resources which are to expand their interpretations, which I have in what I call the “challenge column”, and other resources which help them visualize or simplify, which I put into what I call the comprehension column. I recognize that I limit the choices somewhat, but I would say that the outcome is richer when they have resources to pick and choose from.

I link to videos or outside resources that are thematically interesting; I might use Padlet or Wakelet or Symbaloo to aggregate resources. For example, for the Mount Sinai text, there might be five videos of things being plugged into too much voltage, or things melting down because so much sunlight is being focused on it, or movies that represent the concept of too much power for something to handle. I chose these because one of the themes that the students might choose is that the Sinai experience represents the dangers of too much intimacy or too much connection too fast, which can create a meltdown or a collapsing of boundaries. So, they view videos that might enlighten them on what that might look like. The texts are linked to some resources which are to expand their interpretations, which I have in what I call the “challenge column”, and other resources which help them visualize or simplify, which I put into what I call the comprehension column. I recognize that I limit the choices somewhat, but I would say that the outcome is richer when they have resources to pick and choose from.

The idea of this project or of my class is that we’re taking a text, which is esoteric and which for many of them seems mythical and hard to relate to, and to have them understand that these biblical stories are about us. Students need to decide if this is about their legacy and their history, their community, and their lives right here and right now. For that to be true, they need to have the chance to explore the text and discover how it resonates with them. For some, they get really interested in the idea of the desire for closeness but the fear of what might happen if they get too close, which is one of the ways of looking at Mount Sinai. For others, it might be that relationships need structure and expectations, and rules. And while they may not immediately relate to the idea of a covenant or especially a national covenant, they understand that with their close friends there are rules that they have to follow. Some of those rules are made explicit while others are implied, and they are interested in talking about the rules that govern their relationships and what happens if you break a rule.

Since they have to choose a theme to explore in the text and how it operates in their life—whether through different ways of accessing the text, art, relationships, interviews—they are provided with more options for exploring the text and more access points. It also means more experimenting and exploring and juggling.

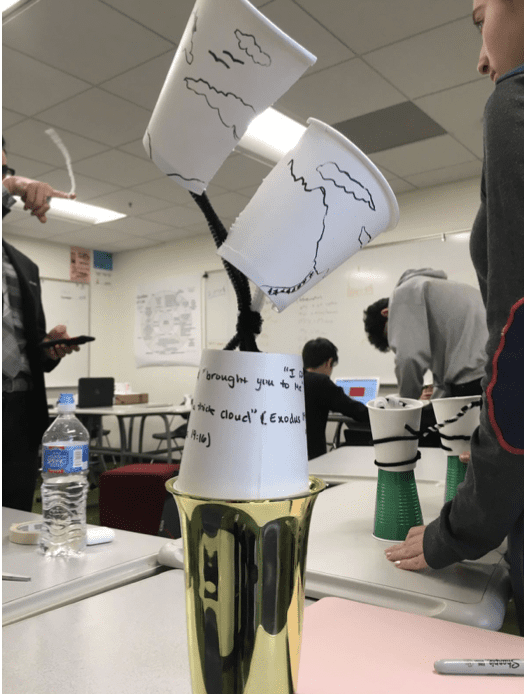

In your instructions, you state very explicitly that the quality of the art is not important. That’s very interesting. Why is that? And do you limit their expression to sculpture? What would you say to a student who wants to express themself in poetry, music, or dance?

That’s a great question. This is a mid-year project, when students are just at the point where they are understanding the idea of multiple interpretations and that there is no single, iconic, or classic way that you have to read the text. Anything goes as long as you can support it with what the text seems to be saying. They’re beginning to understand how they can link to Harry Potter or a psychology experiment and that can be integral to their understanding.

My goal is to have the points of stress be productive and not overwhelming. With that in mind, the artistic component of this is intentionally primitive and there is kind of a limit to what you can do with popsicle sticks, two cardboard cups, two Sharpies, an Exacto knife, and some pipe cleaners. We all know students who do art projects and when they start drawing a picture of the character they very meticulously, for half an hour, make the eyelashes on one of the characters. The idea of primitivity is to help those students—and there are a lot of them. We want them to focus on the ideas, the quality of the ideas, and the expression of those ideas; the execution of the art needs to be deemphasized. For students who say I’m a poet or a dancer or a musician, that creates a different source of stress for perfection in the execution and takes away from the idea itself, which is the opposite of what I’m looking for. The payoff comes when students get it and say, “Oh, wait, this doesn’t have to be perfect,” and then me being able to say: “Not only does it not have to be perfect, do not even aim for that. Make it an effective way to communicate what you’re trying to communicate.” This is an idea I borrowed from Design Thinking.

And I’m serious about that. I want ugly designs. I want ugly scribbles. I want it to be as ugly as possible. They’ll show it to me and they’ll say, “how’s this?” And I’ll say, “It needs to be uglier,” because we want them to get used to the idea that ideas are disposable; I don’t want them getting attached to one initial idea and trying to make it perfect. They’re getting used to the idea of iterations and prototypes. In their next project, they’re going to be building their own Mishkan, like an architecture project. Then they can use Minecraft or clay or cardboard—whatever, go crazy. And at the end of the year, I might be more open to someone who wants to do poetry, dance, or whatever, but we’re ramping up this creative process. They need to first understand that it’s primarily about the idea.

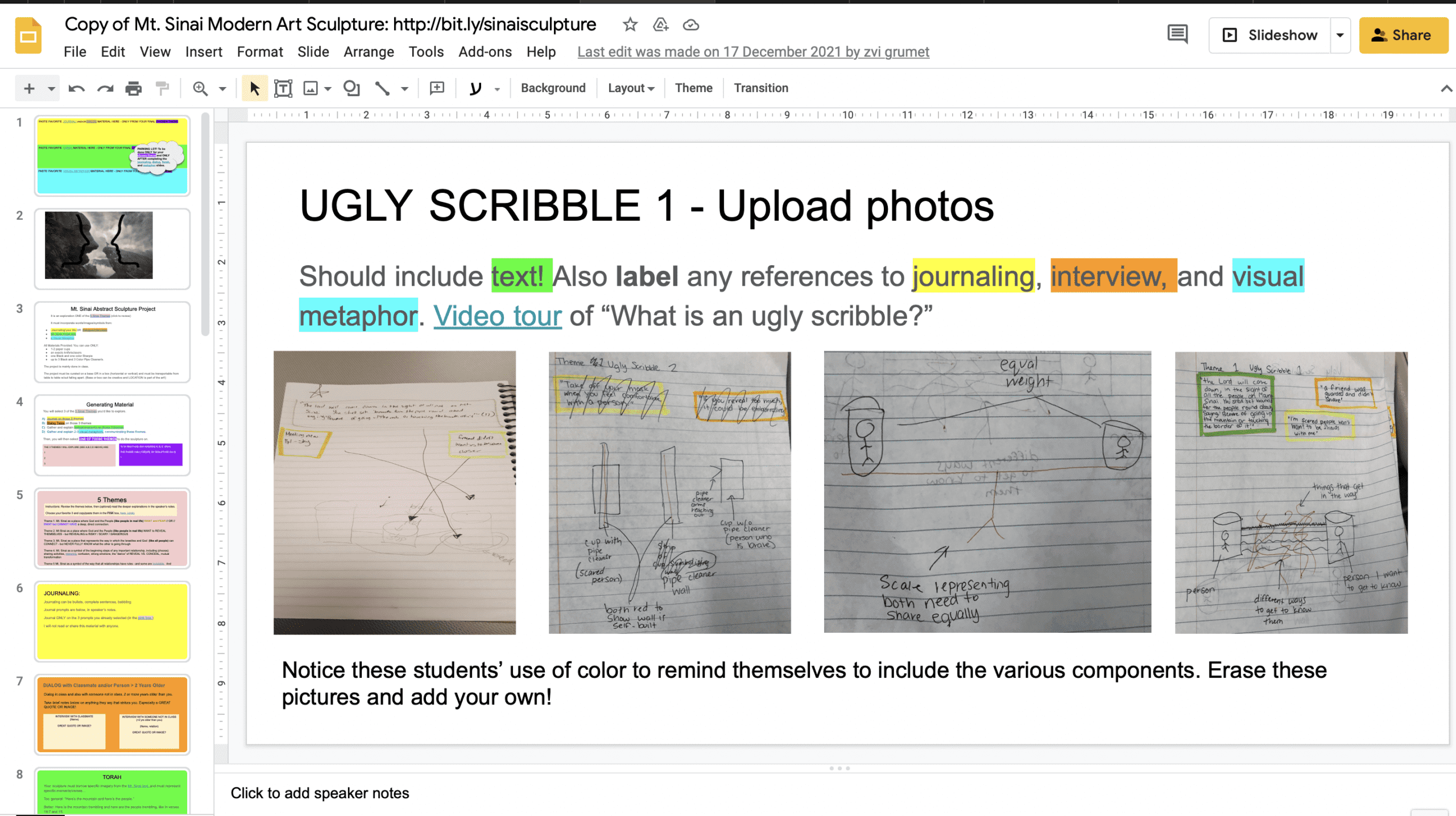

Let’s talk about the slide deck that you give them. The project is presented as a series of slides that are interactive—I don’t think I could describe it to anybody who hasn’t sat and played with it. When we first saw it, we were a little intimidated until we started clicking around and seeing how the pieces connect and interconnect. Are there students for whom the interactive stuff is so overwhelming that they need help with it?

First let’s talk about what this thing is and then address the challenges. For those of you who are seeing a resource like this for the first time, this is a Google slide show, but get rid of the word show. Nobody’s showing anything. Rather, think about a slide deck as a series of pages, and since it’s Google, you can share it with the whole class. Each page of the slide deck has the big box on top and the speaker’s notes on the bottom, which is used like a sidebar with additional comments.

Think of it like a page of Talmud text, with the primary text in the middle and the additional resources around the sides. Everything in both the text and the sidebar hyperlinks to a different slide. For example, one slide focuses on emotions, and there is a hyperlink to that on the first slide which makes reference to an assignment about emotion. And some of the links might go outside of the slide deck to additional videos or whatever other resources they have.

Why do I use it? Imagine that all the material for the project is stored on a series of Google docs, each focusing on a different aspect. Students would have to have five or six or seven different Google docs open at any given time and be jumping from one to the other. Alternately, it could have been a single, long Google doc with sections that are hyperlinked. That’s the way I used to do it, and I’d watch students scrolling up and down over a thirty-page document. I realized how easy it was for students to get lost and decided that there needed to be a better way for them to do wayfinding.

The upside of this is that if a student can’t find the art section, I can tell them to simply go to the green section on the opening slide or the green slide. There are students who immediately attach to this organization and to whom it feels very familiar. They’ve used slide decks in other classes. The downside is that not all of my students get it right away, and it can get overwhelming. For students with issues of executive functioning, it can be challenging, like getting dropped down into a world and needing to figure out how to use it. But every modality that you use—whether it’s a worksheet or a binder or a textbook or parchment—whatever it is, they all have pros and cons. Ergonomically, it’s the best that I have found for this kind of interdisciplinary work with lots of components; it seems to get the job done better than the other things that I tried.

I guess that you really have to play with it to get a sense of how it works. One of the things that becomes clear is that you are looking to create multiple pathways for students. Students can start at different entry points (text, interview, emotion, relationship, etc.) and they have a choice at every step of the way, even though they need to eventually get to the same place or parallel places. We’re really interested to hear more about why that’s so important.

It would be hypocritical if the idea was for students to discover themselves in the text and find their own meaning in the text, but then the way that they had to go about doing it was super rigid. I want the experience of the project to match its ethos. That way, students can choose to work on something for a while, then switch to something else and come back to it later. Or they can build some momentum by doing what they’re excited about. I want the process to match the experience so that it feels personal and that they’ve chosen their own path.

I will say parenthetically that having a huge number of options about the ways that they can interpret the text is actually less important to me. If a teacher said that this is too complicated then I would suggest providing fewer options and a little more direction, like “Study the text first, then do the interviews, then do the visual metaphor,” because they will still have the experience of being at a buffet of interpretations and the logistics of having everyone roam at their own pace. Most important is the range of interpretations and which metaphors they are applying.

For what age or grade level is this?

This is for high school students, mostly tenth and eleventh grade. The number of cognitive and abstract leaps they need to do requires a sophistication that ninth-graders generally don’t have. That being said, the project could be done with somewhat younger students with fewer elements and more structure. Someone who wanted to do something similar doesn’t have to use a slide deck or the interviews or some other component. I do it this way because I’ve been doing this project for a long time, so I can anticipate the mistakes. Even then, I don’t introduce it until halfway through the year after the students have had a chance to onboard into my different techniques.

In terms of designing the project itself, where is the art and where is the science? Are there checkboxes that you’re making sure you’re hitting; are you using a model like UbD or UDL?

I have been influenced significantly by Understanding by Design as a model for setting up your curriculum. Absolutely. And you can see elements of that. For example, introducing the themes early in the year so that students are starting to understand where they might be heading as they go along rather than constantly not having any sense of where this is going. I’ve also been influenced heavily by Design Thinking, and you can see elements of prototyping, disposable design, trying something, and huddling with a group and getting some quick feedback. All those things and the stamps of those disciplines you’ll see in the project. On the other hand, I’ve also been experimenting long enough to discover that rigid adherence to any system often turns into a tail wagging the dog situation where the structure directs the substance rather than the other way around. For example, multiple prototypes are great, but that is not the end goal. So, I might decide to deprioritize an element because it doesn’t fit or because the vibe of the classroom is that they’re getting impatient and we need to wrap up the unit.

For somebody who is feeling constrained by their current way of teaching and that they want to see teaching from a different perspective, Understanding by Design and Design Thinking are great models. But if you’ve been also working with them for a while and they’re starting to feel constricting or like you’re running into obstacles, then you need to find your own pathway as an educator, which is one of the reasons why I’m not suggesting that anybody just adopt this activity. I would hope that someone might be inspired to try a range of different types of things that work for them. The project that I’ve built was built over many years, layer after layer, with smoothing out over the course of time. This project, for example, is probably the result of at least ten years of experimenting, tinkering, and refining built one piece at a time and modified each year.

What advice might you have for somebody else who wants to try to jump in and do something different with their teaching?

It’s sort of like flying a plane, which I do not know how to do. You don’t just get into a plane and start pushing the buttons to try to get the plane off the ground. You have to learn the different components and understand them before you’re going to do the full flight. This is a rather complicated machine; don’t try to just do the whole thing and get it to take off.

What I would rather say is to find something that’s inspiring or interesting and just experiment with it. And it’s a good idea to tell your students, “We’re going to do something that we’ve never done before, and that I’ve never done before. We’ll try it for a day or two. We’re going to see how it goes. We’re going to play with pipe cleaners.” I actually did this a long time ago, and you can still see elements of that in this project, we still use pipe cleaners.

I’m not sure if students liked it; I didn’t really get a good assessment from it, and I didn’t really build it into the curriculum. But it did expand my toolbox, and I eventually came back to it. I think that’s true for teaching in general.

But try one thing and play with it and see how it goes. If you really like it, keep it; if not, then put it in your teacher’s parking lot—maybe later it’ll occur to you to dig it out, rework it, and use it differently. Eventually, you’ll glom together something that works.

How do you envision the relationship between learning projects like this and assessment?

That’s a very good question. The project itself is an experience. I don’t grade the project and students need to understand that because otherwise, they caught up making the little eyelashes. They want perfection; they’re concerned about their grade. The assessment is not the project. You can give them a completion score for doing all the elements or doing all the elements to a certain level of completion. You’ll get a range of quality, but it’s a completion score. Maybe they can fix it if they didn’t finish it and then they’ll get full credit.

The assessment, however, is what you would have them do after they’re done with their projects. It might be something like a one-page bullet-pointed comparison of their project and another one, explaining areas of overlap, areas where they disagreed, and what they learned from doing this. That’s where they are getting off the dance floor and up into the balcony, looking at the bigger picture and seeing themselves in context. Now that they’ve seen another student’s work, that’s where the assessment comes in. Depending on what kind of mode of teaching you’re in, if they’re not trying to compute something, then they can come in and talk with you about it.

You can have informal conversations with each student and you can make sure that they understood it. You can sharpen their thinking so that they walk out of that meeting with full credit because they’ve dropped into it, and you don’t need another test or another assessment after that. They’ve demonstrated in that conversation that they understood their theme, how it’s different from another student’s theme, and how it applies to their life. They demonstrated how having a disposable attitude to their original ideas is really helpful when they’re trying to solve problems.

As a teacher in a complicated experience like this, you have to project calm and enthusiasm. You’re the docent of a museum—don’t worry, just enjoy the walk through the museum. Enjoy playing with the stuff. The assessment will come later. And when they do see the assessment, they’ll understand that it is a reflection of what they’ve done, and students are often comforted by that. At that point, you, as a teacher, can ask the highest-level questions about what the students really took away from this. I think that’s what assessment should really be.

M. Evan Wolkenstein is a high school teacher and author of YA novel Turtle Boy (Random House), winner of the 2021 Sydney Taylor Book Award. He attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Hebrew University, and the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies. His work can be found in The Forward, Tablet Magazine, The Washington Post, Engadget, My Jewish Learning, and BimBam.

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.

Thank you so much for sharing this! I teach Parshat Yitro to 8th grade students, and I am interested in Project Based Learning, so this is great to see!