The world surrounding us (and all the more so, surrounding our students) has become more and more visual in its communication. We are engulfed by logos and icons that we associate with meaning as they immediately conjure in our minds entire worlds of associations, thoughts, and feelings. And yet, we are the “people of the book.” Judaism is text-based and highly values the written word. How can we help bridge these two cultures? How can the two enhance and deepen each other, without being at the expense of the other? Might we, as educators, find ways to both enable our students to become experts at Jewish text, as well as give them opportunities for a deepening of meaning through visual experiences?

The arts are a powerful tool, opening up whole new realms of experience that can significantly enhance Jewish learning, help teachers to reach many more students, and bring a different kind of depth to student learning. Neither students nor teachers need to have artistic talent to explore using art, and the process of learning to bring art into the classroom need not be complex. One easily accessible way of accomplishing this is by using the following framework: See, Do, Share.

See: Refers to viewing and studying art created by a master, and in our case, art designed as a visual interpretation of text. Students, guided by their teacher, try to understand some basic principles which guided the artist in creating their work.

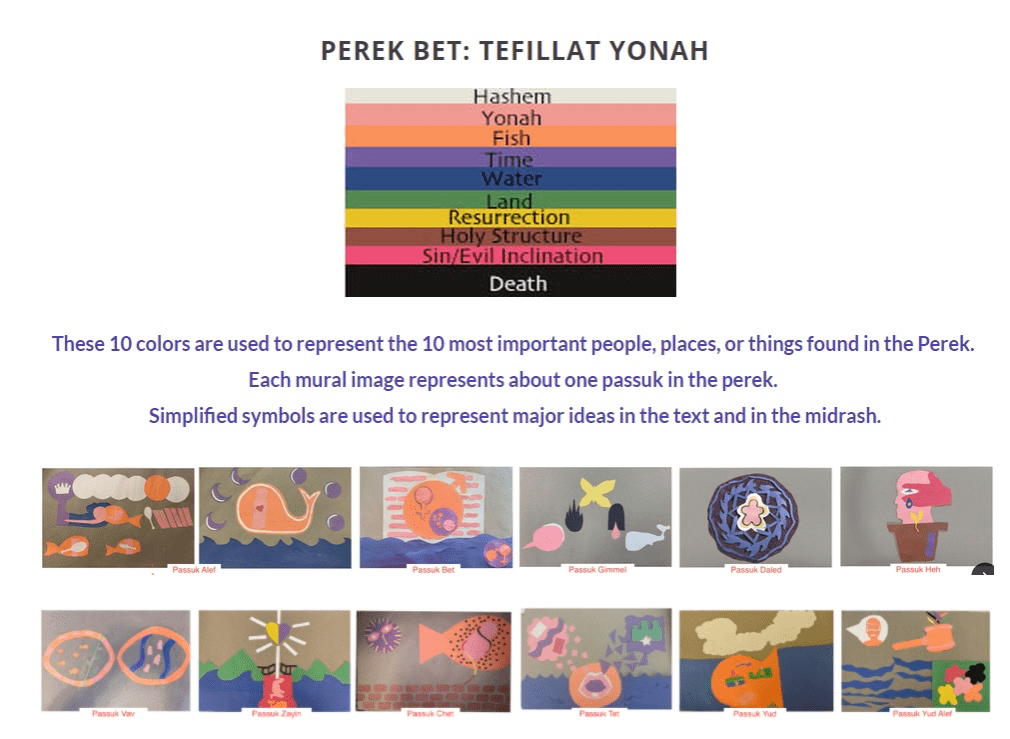

Do: Empowers the students to create their own artistic interpretation of texts using the same principles, the artistic “language” which guided the artist, all while they use their own internal and individual artistic and creative abilities, regardless of what they might be, to create their personal interpretation and understanding of a different Jewish text, idea, or value.

Share: The students share their work with each other, interpret the work of their peers, and together experience the breadth of possible interpretation and expression.

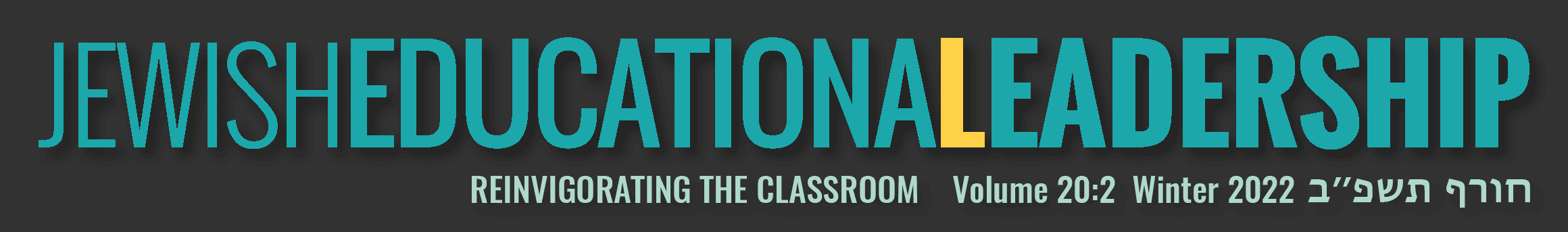

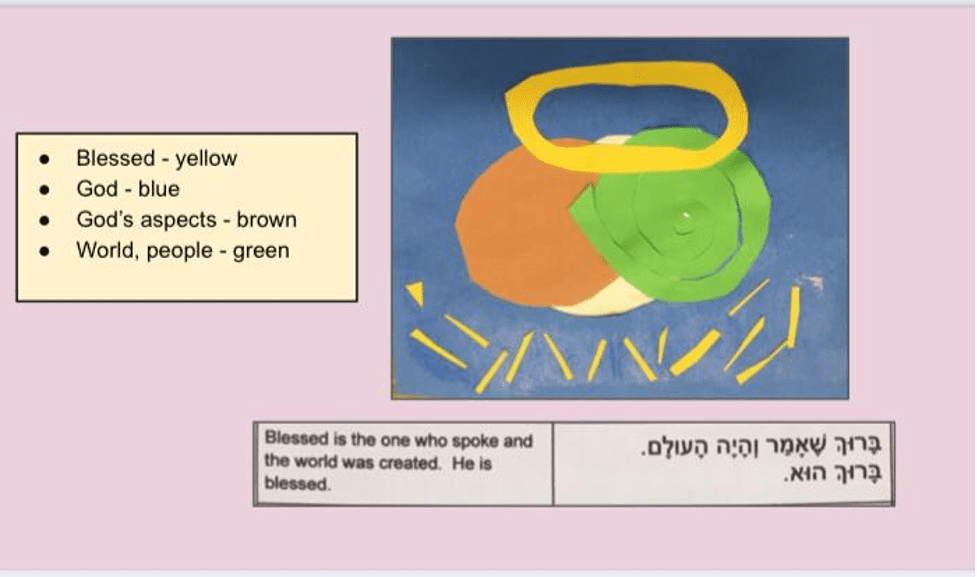

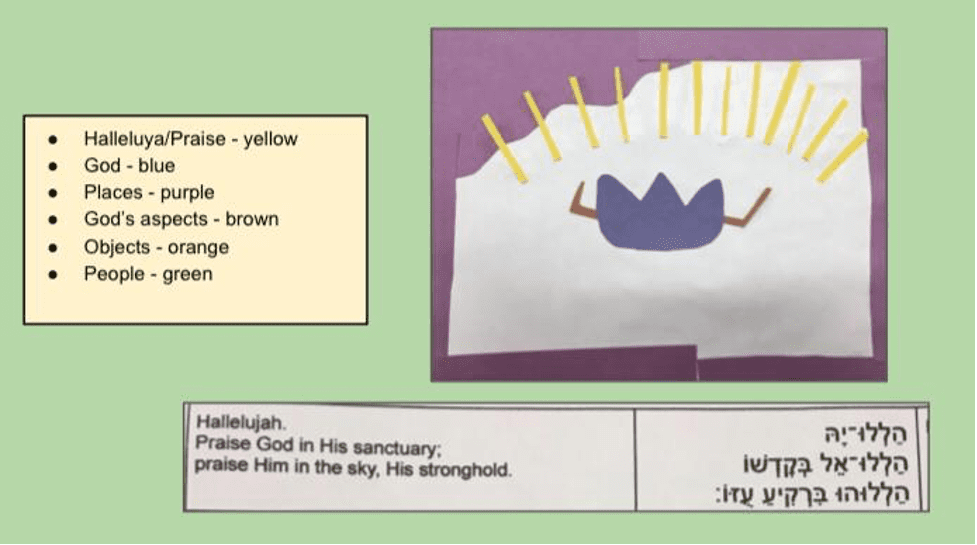

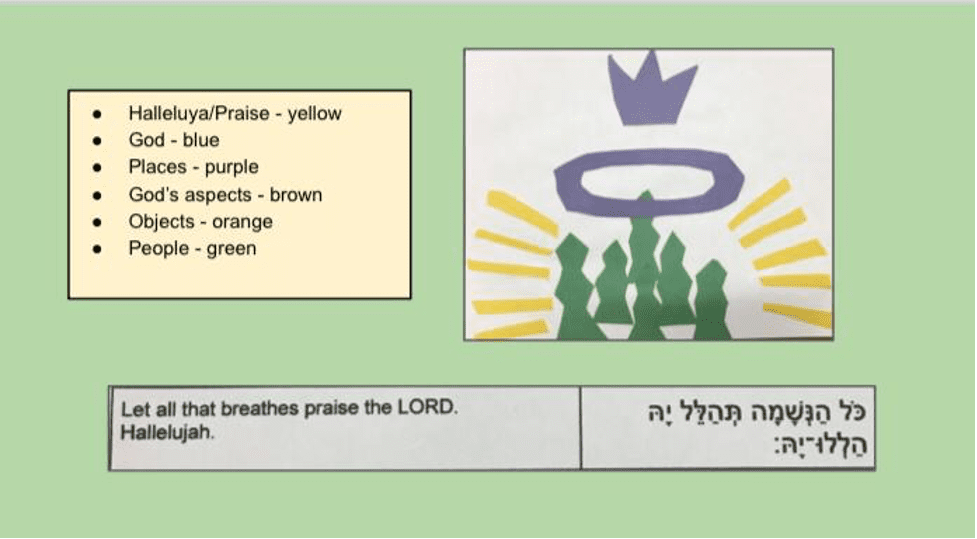

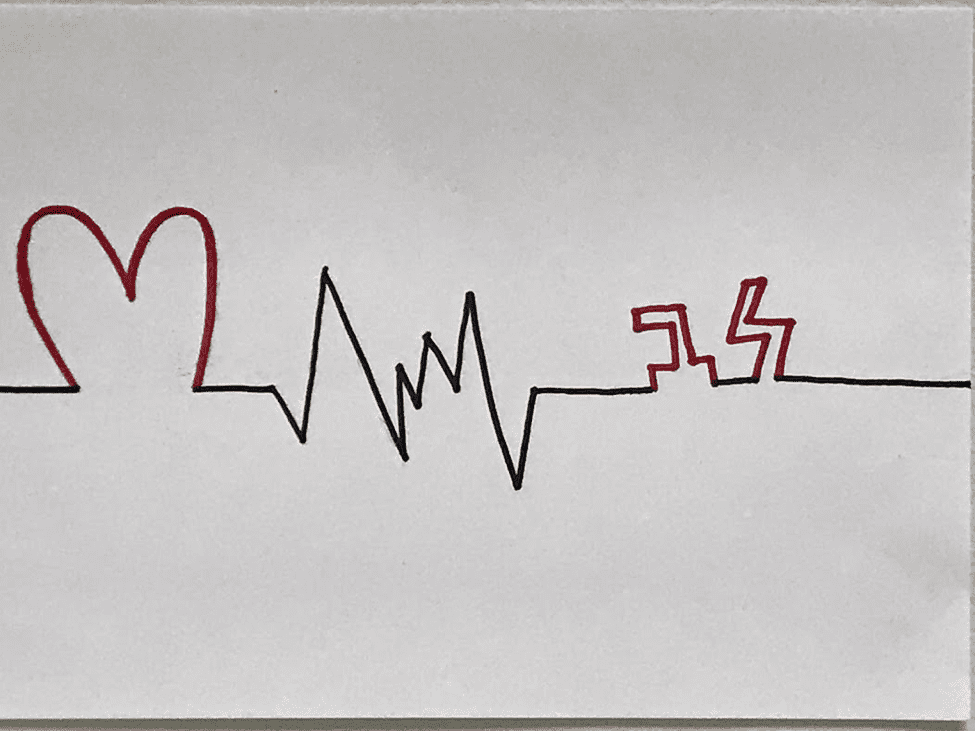

Here is an example that has been replicated successfully, based on a symbolic visual, color-coded “language” that “translates” text to symbols. The students are introduced to a work by artist David Moss: The Binding of Isaac: Genesis 22 (originally created as a mural for Akiba Day School in Dallas, TX), which portrays the entire biblical story of Akeidat Yitzhak using a color code of ten colors. Each character or element in the story is assigned its own color (God is blue, Abraham is white, Isaac is red, Time is yellow, etc.), and the story is “narrated”—phrase by phrase and including a close reading of the text—using striking collages including shapes, arrangements, and symbolic forms. The students, with a little practice, quickly learn to “read” the whole story directly from the images. After immersing themselves in the dynamic visual language of the work, the students are challenged to create their own work using the same strategy on a different text. They now become the artists—they have to carefully analyze the story, determine its major elements, select their own color scheme and take on the role of artists/interpreters/translators themselves. The simple collage style is easily accessible to all students—no previous artistic technique or mastery is required. It is not about the quality of the art, but rather about using the artistic methodology as a form of expression and interpretation.

This kind of activity can be done as an introduction to a new text, to give the students an opportunity to engage with the text directly before they are influenced by more traditional interpretation after they’ve explored more traditional forms of learning, or even as an assessment tool to gauge student understanding of what they have learned.

Teachers’ responses to trying this kind of learning affirm its value and efficacy. As one expressed:

It opens the conversation of the intersection of arts and Jewish studies in Jewish text, and I love how it opens the people who participate to a different way of looking at it.

Or in the words of another:

Take a class of 11th and 12th-grade boys, who were not our strongest learners. … What this did for them was it opened their eyes to the value of art and artistic expression in a way that the vast majority of them wouldn’t have anticipated. Secondly, it gave them a medium through which to connect to their learning and to make it a little bit more personal. It wasn’t just learning ancient texts. It was saying, okay, and what does that mean for me?

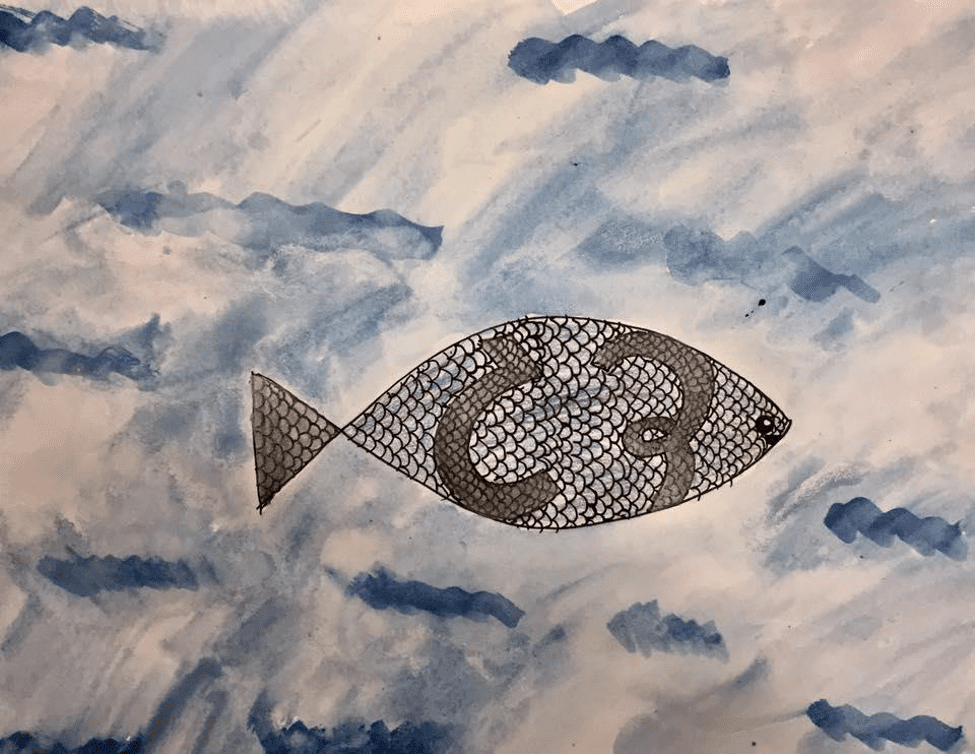

A different example focuses on the connection between Hebrew letters and the content and meaning that the words and letters represent. Here too, we open with professional works of art: Hillel Smith’s Parsha Posters and David Moss’ OMG Bencher are both excellent examples of how an artist can play with the form and shape of the actual Hebrew letters to convey the meaning of the word (or words) the letters are trying to convey. This kind of activity is used by teachers of Hebrew to encourage students to connect the words with their meaning. Words are thus transformed from “random” phonetic symbols to images that visually express their meaning.

Incorporating the arts into Jewish text study gives us a surprisingly powerful opportunity to leap many steps further towards our goal. In the words of one school leader:

This gave them another opportunity to really explore “who am I?” and “what does it mean to me to be Jewish?” and “what symbols represent who I am?” … I think we often ask kids what it means to be Jewish but it’s a really hard question to answer. Sometimes using art as the medium in order to express themselves is an easier vehicle for younger children to begin to connect to that. Then they work on an artist statement so that they’ve got something to kind of work from. When you’ve got a visual, the words seem to flow better.

Just as there is no specific need for students to be blessed with artistic talent, teachers do not need to be gifted artistically. Often, one or two training sessions are sufficient to get teachers started, without the need for an artistic-educator partner, as long as the teachers are open to their own innate internal creativity. The teacher-training harks back to the See, Do, Share model; as the teachers experience how quickly they make the transition into artistic interpreters, they build confidence in bringing their own students into that learning cycle. Obviously, longer training can yield deeper results, but the basic educational approach is easily accessible.

To help facilitate this kind of learning, the team at Kol HaOt has developed a number of “toolkits”— from which the examples described above were taken—easily accessible and adaptable for Jewish studies teachers which can be used to elicit, encourage, and strengthen their students’ artistic expression in the context of Jewish text. These have been tested over the course of the past eight years at a range of schools across a spectrum of grade level and denominational affiliation and are enhanced by additional training through the Teachers Institute for the Arts, a year-long professional development program for teachers in Jewish day schools in North America.

The efficacy of the approach was affirmed by a study conducted by Rosov Consulting which indicated that:

- 94% of responding teachers indicated that incorporating art improved their “ability to make learning Jewish content more engaging for students”

- the teachers’ perceptions were that for almost all of their students the artistic expression impacted positively on their “ability to make personal meaning of Jewish content”

- the majority of teachers felt that it enabled students to connect with texts that had not previously aroused their interest

Ultimately, as Jewish educators, our goal is not only to pass on content and knowledge but to make this knowledge meaningful for our students so that it will become an integral part of their identity and practice. Integrating artistic expression into learning can be a powerful vehicle for accomplishing this.

Elyssa Moss Rabinowitz is Executive Director of Kol HaOt — Illuminating Jewish Life through Art, a Jerusalem-based organization dedicated to weaving the magic of the arts into Jewish educational experiences, as well as the director of their flagship program, the Teacher Institute for the Arts, a year-long PD program for North American day school teachers.

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.