Utilizing Communities of Inquiry to Navigate Challenging Tanakh Texts

Howard Deitcher is a Professor Emeritus and former director at the Melton Centre for Jewish Education in the Seymour Fox School of Education at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Rabbi Dr. Deitcher serves as the Senior Director of Teacher Institutes at the Melton Centre, Hebrew University, and chairs the UnitEd Advisory Committee. He is a member of the Israeli Centre for Philosophy for Children and has published numerous articles, co-edited five books, and produced teaching guides that are being used in schools in Israel and around the world. His current areas of research include: Philosophy for Children in Jewish Education, Spirituality in the Lives of Jewish Students, and Moral Education in the Lives of Young Children.

When addressing morally complex Tanakh texts, middle school educators face the dual challenge of maintaining textual integrity while fostering meaningful student engagement. To meet this challenge, we have introduced “Communities of Inquiry” (CoI), a pedagogical approach rooted in the Philosophy for Children (P4C) movement. These collaborative learning environments allow students and teachers to explore ideas, questions, and ethical dilemmas that arise from complex Tanakh passages.

In this framework, students engage in “doing philosophy”—not as an academic discipline, but as a way of thinking that deepens their connection to Tanakh and to the broader human experience.

This approach emphasizes philosophy as an active, practice-based discipline. It departs from traditional learning models by focusing on intellectual effort, curiosity, and the pursuit of real-life relevance. The process begins with wonder and puzzlement—an invitation to think deeply and make sense of difficult issues. As Abraham Joshua Heschel noted, “Philosophy is the art of asking the right questions.”

A key element of the P4C approach is the Community of Inquiry, which is especially effective for engaging with “troubling texts.” These classroom communities create a supportive space for teachers and students to share diverse perspectives and collaboratively develop rich interpretations. The CoI facilitates meaningful student interaction by establishing structured dialogue where participants build upon each other’s ideas rather than simply debating opposing viewpoints. Students learn to listen actively to their peers, ask clarifying questions that deepen understanding, and practice respectful disagreement that strengthens, rather than fragments, the learning community. Through this collaborative process, learners develop both critical thinking skills and social competencies as they navigate complex ideas together in a safe, intellectually stimulating environment. Currently used in Jewish schools across various countries, this approach offers significant educational benefits as well as challenges, which we explore through findings from classroom implementation.

Core Goals of the CoI Approach

- Meaningful Text Engagement: Foster a personal connection with the text to drive deeper understanding and investment.

- Skill Development: Equip students with tools and strategies for interpreting complex texts.

- Community Participation: Encourage collaborative learning by contributing and learning from teachers and peers.

- Interpretive Confidence: Build the self-assurance needed to offer well-supported interpretations, and the readiness to share with others.

We illustrate this method using Genesis 16—a “troubling text” that raises moral complexities for middle school students. The ancient Near Eastern practice of surrogate motherhood through servants is foreign to contemporary students. Without proper contextualization, students may either dismiss the story as irrelevant or apply modern standards anachronistically. The text presents genuine moral dilemmas with no clear resolution. Sarai’s desperation for children leads her to offer Hagar to Avram, but she later treats Hagar harshly when tensions arise. Avram’s role in this situation also raises questions about his relationships with both Sarai and Hagar, as well as his responsibility toward Hagar and her unborn child. Hagar’s decision to flee to the desert provides another important topic for discussion. Rabbinic commentators grapple with these dilemmas in diverse and often contradictory ways, providing a rich ground for both textual and moral exploration. Some critique Sarai and Avram’s harsh behavior, while others defend their actions as necessary to preserve the covenantal lineage.

In examining this text, teachers must help students understand concepts like patriarchal family structures, the centrality of offspring for inheritance and divine covenant, the role of servants in ancient households, and status differences between servants and their masters.

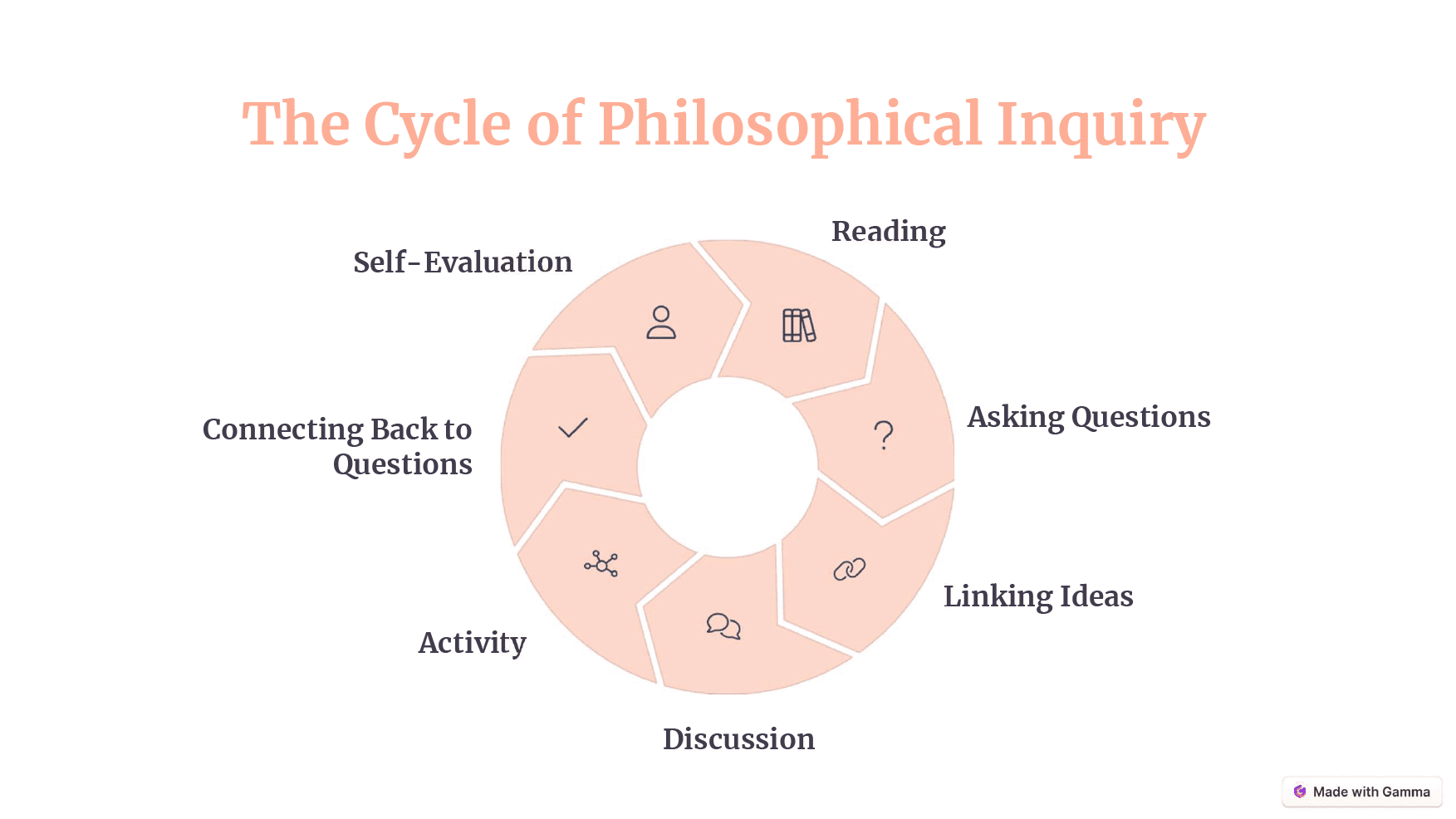

The Community of Inquiry Cycle

The CoI model is comprised of five steps. We will now demonstrate how they can be implemented in teaching Genesis 16 and explain the rationale for each step.

1. Engaging Exercise

Each CoI begins with an activity designed to connect students personally with a central theme from the text. For Genesis 16, examples include the following dilemmas:

- Dilemma A: Avram is caught in a quarrel between Sarai and Hagar. Students reflect on times they were caught in disagreements between two people or groups they care about. What solutions did they consider? How did they handle it? What were the outcomes?

- Dilemma B: Hagar chooses to leave. Students discuss reasons for leaving difficult situations and the difference between “running from” and “going to.”

2. Posing Questions

After reading the text, students note two meaningful questions that arise for them. These are posted anonymously or with their names on a Padlet. This promotes individual reflection and collective curiosity as students share which questions are meaningful for them, and in addition, those that resonate among their peers.

Typical questions that students have shared include:

- Why was Sarai angry at Avram in verse 5? After all, it was her idea.

- What did Sarai mean when she said that “God will judge between her and Avram”?

- Didn’t Avram realize that Sarai’s plan would cause trouble?

3. Linking Questions

Students review all posted questions, identifying patterns and grouping them into thematic clusters. They also name these clusters. This process promotes creative thinking, cognitive mapping, and appreciation for diverse viewpoints. As students examine the collection of questions, they notice unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated inquiries, fostering systems thinking and interdisciplinary awareness. The act of naming clusters requires students to synthesize complex ideas into concise labels, developing their ability to abstract and categorize information effectively.

Through this collaborative analysis, students often discover that their individual questions contribute to larger, shared areas of interest, creating a sense of intellectual community. The visual representation of clustered questions serves as a powerful learning tool, helping students recognize knowledge gaps and identify areas for deeper exploration.

Examples of linking questions for our text include:

- How do we understand Avram’s and Sarai’s behavior?

- What other options did Hagar have for responding to Sarai’s treatment?

- What responsibilities did masters have toward their servants?

This metacognitive exercise transforms simple question-asking into a sophisticated tool for understanding how knowledge is organized and interconnected.

4. Meaning-Making

Meaning-making in this approach operates through a three-stage process that transforms students from passive readers into active interpreters and raises issues that are relevant and meaningful for their lives.

- First, the teacher presents a textual dilemma—a passage posing a challenge, which by its very nature will often generate rich interpretive possibilities. In our example, students encounter the complex relationship between Sarai, Hagar, and Avram through multiple lenses:

- Rabbi Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg, in Haketav Vehakabalah, defends Sarai’s harsh treatment of Hagar by arguing it was justified corrective discipline rather than cruelty. He claims that Hagar became “pompous and acting in a bad way” after conceiving Avram’s child, showing disrespect toward Sarai. Sarai’s harsh treatment was therefore done with a “just purpose”—to bring Hagar back to her proper place and help her understand her role in the household. He characterizes Hagar as lacking moral strength for fleeing rather than accepting this correction.

- Ramban’s commentary on Genesis 16:6 takes a notably critical stance, stating that “Our mother sinned in afflicting her, and Avram also by his permitting her to do so.” This represents Ramban’s characteristic approach of moral accountability for the patriarchs and matriarchs. His interpretation emphasizes the moral complexity of the situation, refusing to excuse Sarai’s harsh treatment of Hagar despite understanding her motivations.

- Nehama Leibowitz first presents Haketav Vehakabalah’s commentary and then argues that, “No appraisal of Sarai’s character could condone the sin of ‘Sarai dealt harshly with her.’” She suggests the Torah teaches that before undertaking morally demanding missions, one should consider whether high standards can be maintained throughout, lest one “descend from the pinnacle of altruism and selflessness into much deeper depths.”

- Second, small group discussions become laboratories for meaning construction. Students don’t simply absorb these interpretations, but actively test them against their own experiences and values. They debate which readings feel most compelling and explore how ancient and modern insights illuminate contemporary moral questions.

- Finally, creative presentations require students to synthesize and express their understanding. Whether through skits, artwork, or digital presentations, the students translate abstract interpretive concepts into concrete forms that communicate their insights to others. This creative process itself generates new meaning as students make choices about emphasis, perspective, and medium.

The meaning-making step recognizes that textual meaning isn’t fixed, but emerges through dynamic interaction between text, tradition, and reader. Students become participants in an ongoing interpretive conversation, creating understanding that honors both classical wisdom and contemporary relevance.

5. Reflection

In the final stage, students reflect individually and collectively on their learning experience:

- The original Padlet questions are revisited, and students vote digitally on the two most meaningful ones. One of these becomes the focus of a future lesson, reinforcing student agency and emphasizing their role as key stakeholders in the learning process. Revisiting their original questions encourages students to once again reflect on how the classroom conversations have impacted and shaped their learning experience.

- Students submit digital reflections on their key takeaways, strengthening the link between text and personal relevance.

- A group discussion follows on the learning process itself: what worked, what was challenging, and how it could be improved.

Conclusion

The CoI approach fosters a classroom culture grounded in textual interpretation, intellectual curiosity, and shared responsibility for meaning-making. This collaborative framework proves particularly valuable when teachers encounter challenging passages in the Tanakh—whether they involve moral ambiguity, difficult theological concepts, or narratives that seem to conflict with contemporary values. Rather than avoiding these complex texts or presenting oversimplified interpretations, the CoI approach empowers teachers to embrace the difficulty as an opportunity for deeper learning. When students encounter troubling passages or raise challenging questions, teachers can model intellectual honesty by acknowledging the complexity while guiding students through a structured process of inquiry. This approach transforms potentially challenging teaching moments into rich learning experiences, as teachers demonstrate that wrestling with difficult questions is itself a fundamental aspect of Jewish textual study.

Furthermore, the CoI framework expands the teacher’s role beyond simply sharing knowledge and introducing textual skills. The educator now facilitates thoughtful dialogue and transforms students from passive recipients into active co-creators of understanding. When navigating difficult texts, teachers using this approach don’t need to have all the answers immediately. Instead, they can facilitate genuine inquiry by asking probing questions, encouraging students to examine multiple interpretations, and creating space for authentic learning. This collaborative exploration helps students understand that engaging with challenging material requires careful thinking, an openness to exploring a range of explanations, and intellectual courage—lessons that extend far beyond the classroom. Many teachers report that by sharing the interpretive process with their students, they create a learning environment where difficult questions become gateways to deeper understanding rather than obstacles to overcome.

Finally, this transformation supports not only deeper Tanakh learning, but also the development of essential habits of mind—such as active listening, openness to multiple interpretations, and the ability to respectfully challenge and be challenged. When confronting morally complex narratives or seemingly contradictory passages, middle school students learn to sit with ambiguity, consider multiple perspectives, and engage in respectful disagreement. These skills prove invaluable when teachers guide students through particularly sensitive or controversial texts, as the collaborative inquiry process teaches students to approach difficult material with both intellectual rigor and emotional maturity. By grappling with the moral complexity of the Tanakh, middle school students are better prepared to apply these skills to navigate the ethical dimensions of their own lives and communities. In this way, Tanakh study cultivates not only more engaged students, but more reflective, compassionate, and discerning Jewish learners who are equipped to wrestle thoughtfully with life’s most challenging questions.

Howard Deitcher is a Professor Emeritus and former director at the Melton Centre for Jewish Education in the Seymour Fox School of Education at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Rabbi Dr. Deitcher serves as the Senior Director of Teacher Institutes at the Melton Centre, Hebrew University, and chairs the UnitEd Advisory Committee. He is a member of the Israeli Centre for Philosophy for Children and has published numerous articles, co-edited five books, and produced teaching guides that are being used in schools in Israel and around the world. His current areas of research include: philosophy for children in Jewish education, spirituality in the lives of Jewish students, and moral education in the lives of young children.

From The Editor: Fall 2025

The year was 1982. I was studying in Jerusalem for the year and my roommate invited me to join him on one of his visits to an elderly recent immigrant from the Soviet Union now living in an absorption center. When we arrived, I was introduced to the elderly gentleman, who told me that his name was Mr. Morehdin (although I suspected that the name was not his original one). While he had a difficult life in the Soviet Union, having spent time in Siberia, he chose to share with us that day how he survived a Nazi concentration camp. One day a Nazi guard summoned him, having heard that he was Talmud scholar. The guard had been told that there were disparaging statements in the Talmud about gentiles, and even laws discriminating between gentiles and Jews in civil matters.

Deuteronomy and the Buddhas of Bamiyan

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were two giant Buddha statues, each well over 100 feet tall, that survived nearly 1500 years until they were obliterated by the Taliban in 2001. The explicit motive of the destruction was extreme Islamic iconoclasm. Almost as soon as the explosions were broadcast worldwide, I raised the obvious connections to Deuteronomy 12:You are to demolish, yes, demolish, all the [sacred] places where the nations that you are dispossessing served their gods, on the high hills and on the mountains and beneath every luxuriant tree; you are to wreck their altars, you are to smash their standing-pillars, their Asherot you are to burn with fire, and the carved-images of their gods, you are to cut-to-shreds—so that you cause their name to perish from that place!

Troubling Texts or Troubling Troubles with Texts?

In the instruction of Biblical or Rabbinic texts, it is quite common for teachers to experience apparent conflicts between the values arising from the texts and the prevailing values of their students. Teachers may feel torn between their loyalty to Jewish tradition that they are expected to impart and their personal and/or cultural identification with the students entrusted to their care. It is my contention and experience that the sharper or more painful the apparent conflict between the values of a text and the values of students, the greater the educational potential. However, teachers need to carefully consider how their own value-orientational ambivalence is playing a role in the educational dissonance—are we really dealing with “troubling texts,” or are we dealing with troubling troubles with texts?

Rebranding God

I’ve been teaching for forty years, mostly to day school graduates. And I’ve noticed something surprising: very few of them have had real educational experiences exploring who God is—or what kind of relationship we’re meant to have with Him. They’re taught about Judaism, Torah, Halakha—but not God.

I won’t explore why that’s the case here, but I do want to talk about the consequences.

We live in a world shaped by beliefs. Beliefs build our reality. They can uplift and energize us—or drain and depress us.

Tanakh’s Challenging Issues: Traditional and Modern Torah Perspectives in Dialogue

Many people view traditional religious and modern critical orientations to Tanakh study as mutually exclusive… Yet, presenting these two approaches as oppositional, with only one holding a claim to the “real” truth, forces students to choose between the curiosity of their minds and the yearnings of their souls, rather than cultivating and nourishing both aspects of their personhood as fully committed Jews living in the modern world. In its best form, Jewish education should involve teaching critical academic and traditional religious perspectives alongside one another, so that students can see the value of both approaches in uncovering the Tanakh’s multivalent meaningfulness and come to embrace the texts of their heritage “with all their hearts, minds, and souls.”

Engaging the Gemara Gap

In my mid to late teens, I became very attached to the study of Gemara. That passion continued for me until, as a twenty-something, I began teaching it to high school students. I soon came to the realization that I did not understand the Gemara in a way that allowed me to successfully transmit its meaning to others. My cultural and religious connection to Gemara had been strong, but not because its contents were fully clear to me. In fact, coming to this realization, I stopped teaching Gemara for a while.Years later, I fell in love with Gemara again. Now, I love learning difficult segments in the Gemara. These are not necessarily morally or ethically disturbing texts. For me, difficult texts are those where meaning-making is not simple; where, as a learner, I will ask: ”What is this Gemara trying to say and why is it here at all?”

A Conversation Across Contexts: A Case for Intertextual Jewish Education

Some Jewish texts are difficult to teach because they demand so much from us and, even more challengingly, our students. They present moral tensions, portray uncomfortable ideas, or raise questions about our faith that sit uneasily with younger thinkers trying to reconcile earlier voices with contemporary values when they feel most comfortable in a space of clear definition. Avoiding these texts can feel easier, but doing so undermines an opportunity for meaningful engagement. When we engage them honestly—balancing yirat shamayim and intellectual integrity—we offer them opportunities for deep learning, not just of content, but of character. I teach both English and Limudei Kodesh at a Modern Orthodox high school.

The King David Hotel Bombing: Eyewitness Accounts as Educational Tools

On 22 July 1946, a massive explosion ripped through the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, leaving 91 people dead, dozens injured, and significant damage to the building itself. Although all three paramilitary organizations operating in the Yishuv had known about this event beforehand, the Irgun was solely involved in planning and executing the attack. This bombing is a critical moment in the history of modern Israel, exemplifying the desperate lengths to which Jews in Palestine were willing to go to confront the British through increasingly military means. At the time, the bombing of the King David Hotel was condemned by many, including the international press and even prominent figures such as Chaim Weizmann.

Love, Gender, and Leviticus

For the final unit assessment of our 12th grade Jewish Studies elective called “Love, Gender, and Relationships,” students had to address the prohibition of same-sex intimacy found in Leviticus 18:22. They could either explore the inclusion of this text in the Yom Kippur Minha Torah reading or respond to a (fictional) friend’s request for advice regarding Jewish practice and same-sex relations. Gabby—a dedicated student who had never missed a deadline—requested an extension because she cried every time she sat down to write.

The Ephemeral Nature of Difficult Texts

This article is neither a record of success nor of unmitigated failure. It is a reflective description and evaluation of my experience, which I see as part of my own professional growth and which I share in the hope that it will be of help to other teachers. I should add the caveat that this reflection is happening much too soon for reliability. My standard line to students is that I judge my teaching by the condition of their souls ten years afterward (and I love it when they call to let me do that).Nearly three decades ago, I taught the book of Jeremiah in a Modern Orthodox high school. I identified ways that the text might challenge my students and planned my teaching around them.

Three Hashkafot, One Torah: Teaching Challenging Jewish Texts about Women

It is impossible to learn and teach Torah without encountering texts that relate to women in challenging ways. Contemporary conceptions of women’s roles and rights chafe against stories and laws in the Tanakh and Talmud, the historical development of halakha, normative prayer practices, and underlying assumptions in philosophical works. In this brief article, I do not attempt to soothe these tensions—that is far too great a task! Rather, I seek to offer the reader three conceptual frameworks—hashkafot, if you will—through which we tend to approach this tension in Orthodox day schools. Each hashkafa is described in the full-throated voice of a proponent of that lens. Then, I discuss some potential tradeoffs of using each conceptual framework in a Judaic studies classroom.

Using Context and Subtext to Unpack the Text

Teachers of Torah texts in the day school setting are bound to encounter a text that contains content that is difficult to teach. It can be especially difficult when the text seems to be working from a framework of values or interests that are distant from the current moment. Or, it may just be too heavy a lift to explain to students what a particular text or story was trying to accomplish when the students only notice a bothersome turn of phrase. With attention paid to context and subtext, a text that initially seems troubling may show depth that makes teaching it not only possible, but essential. An example of this can be found on Kiddushin 49a-b. The Gemara begins a discussion about how to make sure a man has fulfilled a condition he set regarding his own character traits in order to accomplish the transaction of kiddushin.

Shelo Asani… Navigating Prayer Practices in a Modern Orthodox School

Oakland Hebrew Day School is a Modern Orthodox school that draws from a wide range of religiously diverse families. With our enrollment coming from (and relying on) a diversity of affiliations, our commitment to maintaining our Modern Orthodox identity sometimes creates complications, particularly in the realm of our tefillah practices. Many parents don’t have personal prayer practices, and for parents who do, some use liturgy or have traditions from different denominations. Like many schools, we have a siddur ceremony in the 1st grade in which students receive their own siddurim. As an Orthodox school, we distribute Orthodox siddurim (we have been using the Koren Youth Siddur).

Struggling with Form and Feeling

Over a delectable meal during Hanukkah in 2012, Professor Gerald Bubis told me about a sermon he had heard at Valley Beth Shalom in Los Angeles. In it, Rabbi Harold Shulweis passionately insisted that kashrut practices must be rooted in ethical consciousness. “The Jewish theology of kashrut is not pots and pantheism,” Shulweis poetically preached from the bimah in 2009. Jerry spoke to me not only as a budding Jewish educator, but also as a future family member, encouraging me to balance halakhic rigor with spiritual depth. He railed against mechanical or performative acts, in all arenas. This was one of our earliest and most memorable conversations. Thirteen years later, while teaching a capstone course in modern Jewish thought to high school seniors at Rochelle Zell Jewish High School, I found myself reflecting on that encounter.

f_25 template

Every other Friday, the 9th grade Jewish Studies classes each sit in a circle in the middle of the room. At the front of the room, a neatly pressed white cloth neatly covers a table with two Shabbat candles and two snacks. We start the period with a song and then dive into the heart of the student-led activity. This is what the kids have come to know as “Jewish Journey Friday.” After lighting candles and distributing snacks, the two students hosting that week each ask a carefully constructed question. The questions are designed to elicit a specific and personal story that will reveal some element of a person’s Jewish Journey. “Tell a story about a particularly memorable Passover experience.” “When was a time when you felt particularly proud to be a Jew.” “Tell about a specific way in which you see your Judaism differently today than you

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.