As Jewish educators in 2021, we are educating learners who are coming of age during a disturbing resurgence in antisemitism and anti-Jewish sentiment. The choices that they make about how to present Jewishly in public are at once deeply personal, while also being a matter of collective concern and communal soul searching. After all, we as educators champion having pride in one’s Jewish identity. It only makes sense that a generation of individuals who are proud, engaged, and confident in using their voices, would be excited to show their inner selves in their external appearances. At the same time, the uptick in antisemitism that has colored the coming-of-age experiences of Generation Z-ers over the last few years has sometimes resulted in adolescents who are more comfortable keeping their Judaism inside.

Rachel is a high school sophomore from Texas. She has been involved in her synagogue, but generally walks through the halls of her public school knowing that she’s one of three Jews in the building. Rachel shared the intentionality behind her decision to wear a particular Jewish symbol. She decided to wear a chai necklace, a symbol of Hebrew letters representing the word meaning “life.” By opting for this symbol instead of the better-known and more easily recognized Star of David, Rachel sought to use her sartorial choices to start conversations. “I got the chai because it’s a way to show my faith to others. People who aren’t curious won’t ask. But because it’s not a Star of David and everyone doesn’t know what it is, if they’re curious enough and they do ask, there’s room for us to have a conversation.”

Zachary is a student at a Jewish day school in Maryland. “After the shooting [at Congregation Tree of Life in Pittsburgh] I started wearing my kippah more in public. I take the metro to school every day, and I wear my kippah. Sometimes I run into other Jewish people, and it’s fun to have a connection. But I understand people who are scared of something happening when you look Jewish in public. For me, I feel like it’s better to show that we’re here, we’re not going anywhere, we’re still Jewish, and we’re going to stay Jewish. There’s not anything anyone’s going to do about it.”

As Jewish educators, we often describe part of our mission as meeting learners where they are. In the case of today’s adolescents, that can mean any number of things, including showing up in person, on Zoom, and on an ever-changing array of social media platforms. Adolescents spend their time in a combination of in-person and virtual spaces, and in each environment there are choices to be made about what it means to present as Jewish. Lia, a high school senior from Ohio, shared that, “I used to include lots of stuff about being Jewish online. I love baking hallah, and I’d put it in my Instagram stories, and I had a TikTok go viral about lighting the Hanukkah candles. But then I started getting hate. I’d post something about Shabbat, and people would tell me to go into the ovens with my hallah. So, I stopped displaying myself as specifically Jewish. Now I’m just someone who bakes bread.”

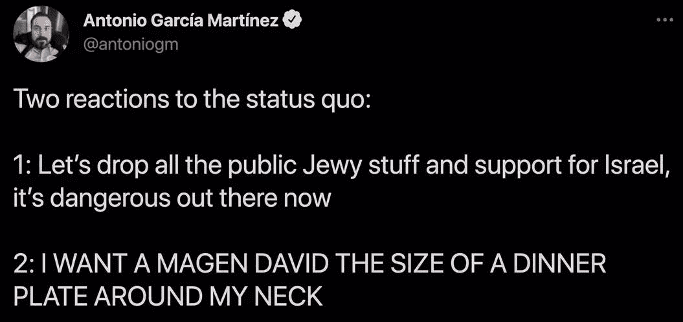

In June of 2021, a meme circulated on social media:

When it comes to presenting Jewishly in public, every choice that each individual makes is deeply personal and legitimate. If someone is frightened for their safety when they claim their Judaism in physical ways, or if they don’t want to be on display as representatives of the Jewish community and opt to fly under the radar, this is not indicative of Jewish shame. Rather than being a commentary on the individual, it’s an indictment of the society that creates the environment in which we feel that being a Jew is something that needs to be somehow private. Likewise, for those who choose to present loudly and proudly, this can be a beautiful thing, particularly when it’s done for the right reasons. To show one’s pride is great—when it’s on your own terms. But for someone’s Judaism to manifest purely as a statement of defiance to detractors is its own potentially fraught reality.

The decisions that adolescents are making about presenting Jewishly in the face of rising antisemitism are informed by instinct, lived experiences, and social norms. Part of the role of the Jewish educator is to be a conduit for this transference of Jewish pride. Our pedagogy can help shape and influence if and how our learners choose to claim their Judaism in public and virtual forums. In our work, we regularly share the beauty, complexity, and meaning-making that Judaism provides. But are we intentionally connecting the lived experiences of Judaism, however they manifest for our learners, with what it means to carry oneself Jewishly in a world where that means being a minority, visibly or otherwise?

“Judaism should be a joyous experience. Antisemitism isn’t, and shouldn’t be, our major raison d’etre when it comes to being Jewish. We take it seriously, of course. But if it becomes what defines our Jewish identity, they win.” Lily, a high school senior, summed up her perspective succinctly. Pride is encouraged and championed, always. But a Judaism based on defiance is neither sustainable nor transferable. If the response to antisemitism is focusing all of our efforts on countering hatred and detractors, learners may find real meaning in their activism and self-advocacy, but they run the very real risk of losing sight of the why behind the what. Any identity that is based on what it runs counter to, rather than the value that it brings lacks sufficient grounding. So when Jewish sartorial choices are made, whether they are for religious observance or cultural adherence, their value to the wearer comes from how they experience embodied Judaism, not in how others react to their choices.

People have lots of guesses about what the hardest and best parts of our jobs as Jewish educators are. Among the elements that others consider to be top contenders for the hardest, there’s recruiting participants from an over-programmed population, dealing with the sometimes conflicting demands of parents and learners, never having enough time, and limited resources. All true. Likewise, some of the top guesses about the best parts are making an impact on young people, constantly learning new things, participating in immersive experiences, and being able to align my passions, values, and profession. Again, all true. But the at-once hardest and best part of this job is being an authentic Jewish personality, a role model, with flaws and questions and ingrained truths, that our learners can relate to, and be challenged by, and learn from.

For those who are coming of age during the resurgence of hate, and those who care about them, allowing for the gray area between the black and white of right and wrong to be a place of meaning-making will be critical. So too will be finding the authentic truths that guide them in their life journeys. As for where that leaves the status quo with regards to antisemitism, the story will continue to unfold.

Reach 10,000 Jewish educational professionals. Advertise in the upcoming issue of Jewish Educational Leadership.

Do you want to write for Jewish Educational Leadership? See the Call for Papers for the upcoming issue.

Understanding the New Antisemitism with Yossi Klein Halevi – 2024 Update 📄🎬

I think we’re experiencing a phenomenon that we can call massacre denial or massacre trivialization. And I don’t like Holocaust comparisons to Israel’s situation. But in one way I do believe that a Holocaust analogy is legitimate and that is in in how the historicity of October 7th is being treated and the uniqueness of October 7th. What makes October 7th unique is that it was not a pogrom, these were premeditated atrocities. And the purpose of the atrocities, was to instill terror. So what is happening to the memory of October 7th, the understanding of what October 7th was, is very similar to what Holocaust memory has been subjected to in large parts of the world.

From Fear to Resilience – 2024 🎬

The whole world has changed. I feel like we’re at a historic moment for the Jewish people. This is one of the major, major dividers within the Jewish world today. Those who have never really known Jewish vulnerability and those who know it and feel a deep in their kishkes. And I think that divide has been kind of blown up right now. We’ve known through the statistics that antisemitism has been on the rise for the last many years. And I think Pittsburgh, Tree of Life, really changed in some ways the American Jewish condition. It kind of woke us up to the fact that it can happen here.

Building Jewish Strength – 2024 🎬

I think among the things that are concerning for me is that the people that I work with, and I’m in a Reform congregation, we’re a very large community with a lot of diversity within that community. I think that what is particularly concerning to me is that our people are so caught off guard and surprised. That all of the sudden in 2023, all of the sudden it’s as if there wasn’t antisemitism before October 7th. We either had our heads in the sand or we were just kind of in a position of not really acknowledging the extent to which antisemitism is still a part of the human existence. I won’t say the Jewish existence because I think antisemitism and anti- antisemitism is more than a Jewish concern.

Confronting the Campus Crisis – 2024 update 📄🎬

I think what we’re seeing now is a globalization of antisemitism and it’s become a mass movement in the name of anti-Israel activism, in the name of anti-Zionism, which is not to say that anti-Zionism automatically equals antisemitism, but the way that anti-Zionism is expressed particularly now, is in an antisemitic way. One example, for instance, maybe you would a draw a Venn diagram and you would have a big circle and that big circle says criticism of Israel. Then you have another circle, which is antisemitism, and then you have a bit of an overlap. And the overlap seems to have increased recently. Why that is, is because Hamas is in itself an antisemitic organization.

Antisemitism, Debating a Lie – 2024 🎬

The most concerning thing I find about the uptick in antisemitism is the lack of knowledge on the part of Jewish students and others about the real history of the situation. The kids don’t know how to have a cogent debate. They don’t have the knowledge. They don’t have the history to truly stand up and speak truth to lies. And that actually is the most disturbing thing. If there’s violence, it’s obviously extremely disturbing. But I’m not as worried about that as the long term issues, both on college campuses and now on high school campuses, where the lack of knowledge and the level of ignorance is so profound that I think we are in a strategically dangerous spot with our youth who don’t know.

Seeing Antisemitism Clearly – 2024 🎬

The time when my thinking on antisemitism changed the most in the last five years was actually 2021, not now. In 2021, we had a similar situation on a smaller scale to what we have now, which is Israel and Hamas fighting and violence against Jews outside Israel. Hate crimes, attacks both at protests but also just on the street. And the thing that changed my thinking the most was not fighting in Israel and was not even those attacks. But it was how the reaction to those attacks from people who are most likely to stand up for minority groups who are being subjected to racism or prejudice was anything ranging from apathy to justifying or contextualizing the violence.

Antisemitism – So Close to Home – 2024 Update 📄🎬

I appreciate the opportunity, unfortunately, to revisit the question of antisemitism and the Jewish day school landscape. And it was almost like looking back at an innocent time to think about the Pittsburgh experience, which is what I wrote about, the proximity of my experience to the three congregations that were massacred in the Tree of Life building. At that time I definitely had it in the context of, well, I’m not surprised. I’m a child of Holocaust survivors. This is going to happen periodically. The big difference was the feeling that the world and the communities and the rational universe were very empathetic and sympathetic to what happened to the Jews in our community.

Antisemitism and Identity – 2024 Update 📄🎬

So the question was, in the last two years, has your thinking on antisemitism changed? And the answer is very straightforward. My thinking has not changed whatsoever. I knew that antisemitism is an issue, even though people around me have been minimizing and denying it and now it’s just out. It’s clear that there is bias even among people who are not necessarily antisemitic. It seems like there is a radicalization among younger people. I’m wondering to what extent education has to do with it. I got my Ph.D. here and I’ve seen the environment. There seems to be also a lot of misinformation at least on the school campuses or university campuses.

Caring for Our Students & Ourselves in the Face of Antisemitism🎬

Jewish educators are dealing with antisemitism on two levels. We are dealing with our own shock, fear, anger, and uncertainty. And at the same time, we need to be able to address antisemitism in our classrooms, camps, or youth groups. We need to help our students feel safe and supported, and we need to make sure they have some tools in their arsenal to rely upon. While there are so many questions, many without answers, there are some things that we can do right now to help our students feel safe and supported. This series of videos from The Lookstein Center at Bar-Ilan aims to give educators tools for helping our students through these troubling times.

Antisemitism is Systemic, and Yet Deeply Personal – 2024 Update 📄

In the United States and across the globe, there is an all-out assault on Jews arising from the political left, political right, and seemingly everywhere in between. From virulent and overt violence to the dog whistles of antisemitic tropes, one can see antisemitism alive and growing in almost every facet of life. In a survey conducted by ADL, over 1 billion out of 4 billion people surveyed across the world harbor antisemitic attitudes. That is over 25%. As the Program Manager for Echoes & Reflections, my career is focused on helping secondary educators effectively and responsibly teach about the Holocaust and contemporary antisemitism.

Insights From College Guidance in the Wake of October 7th – 2024 📄

I have been privileged to work at SAR High School since 2007, assisting many hundreds of graduates with the college admission process. It has been a true labor of love, helping a student discover the institution that could be their perfect match for four transformative and memorable years. Front and center in the admission process has always been a student’s growth as a Modern Orthodox Jew, with considerations like kosher food, daily minyanim, Hebrew language and Jewish studies departments, Torah learning opportunities, and Israel advocacy coming into play as much as academics and student life.

Reflections on College Guidance after October 7th – 2004 📄

This all happened at a very interesting time in the college application cycle. When the war started and we started seeing anti-Israel and antisemitic activity happening across the country, our immediate thought in the Milken college admissions office went to students applying early decision to schools, because that’s a binding contract—if you’re admitted, you have to attend. October 7th was a month before early decision, early applications were due, and we had to do triage for those students. For students who were not applying early decision the timing wasn’t as critical.